How is salt harvested?

There are essentially three ways to obtain table salt.

Salt can be mined.

That’s what’s done for Kosher salt, which is mined in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, a salt that’s often recommended in cookbooks. Mining is pretty much the process you imagine. It takes place underground, there are big machines and a lot of noise. Mined salt is purified and often has additives to prevent clumping. Iodine is also added, a public health initiative to prevent goiters. Tasted next to sea salt, I often find mined salt to have bitter, metallic flavors.

Salt can be boiled out of seawater.

This is what’s often done in cloudy, moist, coastal places. Seawater is slowly cooked, like soup stock, until the salt naturally crystallizes. The crystals form pyramid structures that have a satisfying crunch. This salt is not treated any further and can often be a startling shade of bright white.

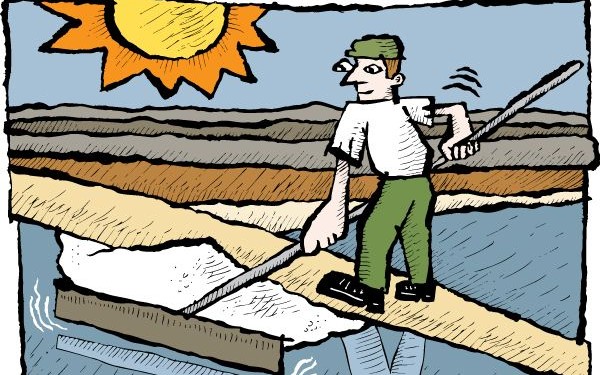

Salt can be dried out of seawater by the sun in shallow pools.

This way has the most history. Given that it’s almost entirely “solar powered,” it’s the most natural, environmentally sensitive process. Typically, nothing is added. Its color can range from near grey to titanium white depending on the makeup of the local water.

Traditional salts like these can have great differences from one to another. While salt is primarily sodium chloride, the other elements present in the sea, some of which make it into the salt, add flavors. From Portugal’s Algarve to Sicily’s Trapani to France’s Brittany, the colors and flavors of the salts gathered in each area are very different. There are also textural differences, usually the result of grain size or harvest method.

Sea salt’s typical harvest method is shovel and wheelbarrow. The pools dry and look a bit like frozen ponds. The salt gatherers chip into it like they would into ice. However, in some areas, like Algarve and Brittany, there is a second method. Gatherers use rakes to collect the salt off the top of the water before it solidifies. This is called the flower of the salt (fleur de sel in French, flor de sal in Portuguese). It has a texture like crunchy snowflakes and is prized for its delicacy.

The story behind sun dried foods

Sun drying is the oldest food technology still in use today. (I believe it predates fire, but hey, I could be wrong.) It’s not too common these days, since cheap electricity allows us to dry things much more quickly than the sun does. But sun drying can produce some incredibly flavorful foods including some of our favorites like sun dried tomatoes, couscous, peppers, and salt. And it can do so in an incredibly environmentally friendly way.

The first sun dried foods were a product of necessity.

Removing moisture helps to preserve food, and also made it lighter to carry, two reasons why the nomadic Berber peoples of North Africa started sun drying foods thousands of years ago. By processing wheat into sun-dried couscous they were better able to have a ready food supply, even if they had a year or two of bad crops. The fact that slow sun drying can also produce a lot more flavor must have been a bonus; the sun dried couscous made by the Mahjoub family in Tunisia is toasty, wheaty, and way more flavorful than any other couscous I’ve tried. The sun dried garlic spread that the Mahjoubs make is likewise deeply flavorful. The time it takes for the garlic to dry in the sun concentrates its flavor, enhancing its natural sweetness—the same sort of effect you get from roasting a head of garlic in the oven.

That intensity of flavor is a common theme amongst sun dried foods. Marash pepper from Turkey is a prime example. After being harvested in August, shiny red peppers are laid on white muslin sheets to dry in the sun for a week. The type of pepper used is prized because its thin flesh can dry fairly quickly; thicker peppers end up with a tougher texture. After drying, the stems, seeds, and white interior flesh of the peppers are removed, which reduces the heat level but maintains the flavor. The result is a burgundy pepper flake with a deep, roasted chile flavor that lasts and lasts without ever getting too hot.

This ancient technology is up-to-the-minute environmentally friendly.

The counterintuitive thing about sun dried foods is that, even when they’re shipped to us from the other side of the world, they can be more environmentally friendly than local foods that rely on more energy-intensive methods to create. Take salt, for example. To make salt here in Michigan we have to mine it with heavy machinery (that’s how the Kosher brand salt you see at grocery stores is made—it’s mined just north of Ann Arbor). To make it in foggy coastal places like Wales you have to boil it out of the sea water, which takes a tremendous amount of fossil fuel. But on the sunny Southern coast of Portugal or along France’s Brittany coast, salt can be harvested from shallow pools of sea water that evaporate in the sun. The salt is raked by hand and the only machine you’ll spot is a conveyor that piles it high for storage until it’s shipped to us.

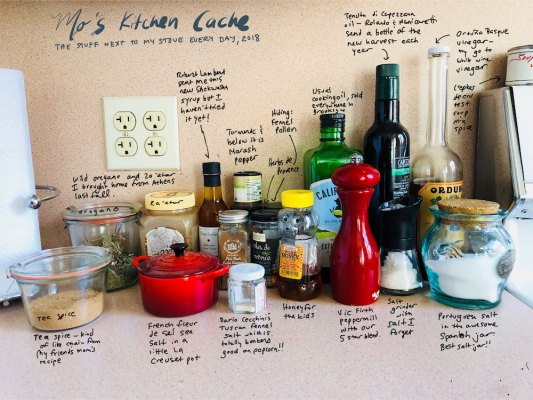

Mo’s cache of kitchen staples

The counter to the side of your stove. It’s where you keep the foods you need most often. The ones you grab every day. Your kitchen’s speed dial. Your food friends list.

Here’s a written snapshot of the space next to my stove.

So many salts

I’ve probably got too many salts. They all have a reason for existing but I’ll admit it, I’ve kind of got a problem. There’s coarse salt for boiling or braising. There’s fine salt for finishing a dish, usually the one I import from Portugal. And French fleur de sel for when the salt really has to shine. I’ve even got one flavored salt these days, from Tuscan butcher Dario Cecchini. It finds its way onto popcorn (frequently) and other dishes (sometimes).

Pofi wine vinegar

Most of the time I make my own salad dressing: vinegar + oil + Dijon + salt + pepper, takes about 2 minutes. I also use wine vinegar to deglaze a pan and make a little pan juice to drizzle on whatever I cooked. Pofi has been my go-to for years, the great barrel aged wine vinegar from near Rome.

Marash red pepper

The counter next to my stove hasn’t been without a jar of these red pepper flakes for 20 years. Sometimes I put them in the freezer (they keep more moist that way, I really should keep them there), but whatever, they sit here now, and God willing, they always will.

Olive oils

I’ll be honest, this is always a hodge podge on my counter. I am lucky enough to have lots of olive oil samples come my way. I always keep an oil that’s for finishing. Sometimes two. One spicy and green (right now I’ve got a tentacle bottle from Puglia that we sell in different one-of-a-kind handmade bottles each year), one mild and sweet (currently Alziari). For my cooking oil, I usually buy California Ranch from the grocery store.

Fennel Pollen

My partner Ari called fennel pollen “fairy dust for food lovers,” a couple decades ago when we first discovered it and that’s still the absolutely best way to describe it. I put this on dishes just to see what it’ll do. Usually it makes eyes light up.

Finds from traveling

I always pick up something that’s easy to bring home when I’m traveling. From recent trips abroad I have a jar of dried Portuguese pepper, what they call pimentao, from Lisbon, and some Greek oregano and za’atar from Athens. I use these like I do the fennel pollen: put them on a dish, see what happens. It’s a fun way to cook. When they’re gone I’ll seek something else on some other journey.